Claude Berri’s Le vieil homme et l'enfant (1967) (commonly referred to by its American title The Two of Us) is a fascinating look at an unlikely relationship formed between an old, anti-Semitic man Pepe and a young Jewish boy named Claude. This type of material, in the wrong director’s hands, could quickly turn schmaltzy, mushy, and sentimental. But, in Berri’s competent hands, it feels very naturalistic, not forced, and allows us to look beyond the surface into some of the deeper truths the film conjures up. With the exception of some of the musical score choices, gone are most semblances of that sort of Hollywood heavy handiness, replaced by a camera that doesn’t impose a viewpoint, but allows us watch a tender bond formed before our very eyes. Examining and analyzing different aspects of the film, what it may have done both successfully and not, will provide a deeper understanding on its overall effect, and in historical context, its rank among the more important films dealing with the Holocaust.

To get to the core of the film in as succinct as way as possible, the most telling line delivered in the film is by young Claude, who asks, “Why doesn't he like Jews if he is nice?” This, on the surface, a relatively simplistic and childlike question of naiveté, actually strikes much deeper than its straightforwardness may suggest. On a deeper, psychological scale, Claude’s innocent inquiry is a very rational, even logical, question to be considered. Why does Pepe so blindly hate? This question is complicated further, as throughout the film, with the exception of his anti-Semitism, Pepe is portrayed as a rather kind man, full of many good traits and ultimately very likeable. Pepe is a vegetarian; he fiercely refuses to partake in the usual dinner selection of rabbit. They raise rabbits on their own land, animals which Pepe looks after sweetly, cooing and pampering as if they were his very own personal pets. Pepe also has a dog, one much beloved, that we regularly see Pepe feeding with a spoon at the dinner table, as if the dog was a regular member of the family. It’s clear the dog has served as Pepe’s closest ally and friend, as the film progresses we see Claude moving into that position, as now, Pepe not only has a confidant that will listen, but also ask questions and interact with him. So, returning to the aforementioned question, why does this caring old man hate Jews? He even says himself they’ve never done anything to him personally. The answer, unfortunately, isn’t as cut and dry as a simple explanation. I think that holds true for many during the time of the Holocaust itself, who, without all the reliable information, weren’t sure what or how to think, not until later, when the truth was revealed, really understanding and starting to comprehend the atrocity.

Another way Claude gets about asking the same sort of moral question is bringing religion into the conversation. Pepe is a religious man, we see him attending Mass, and yet, certain ideological truths, when confronted with them, leave him bewildered and dismissive. This is showcased quite beautifully in one exchange between the two central characters:

Claude:

Was Jesus a Jew?

Pepe:

So they say.

Claude:

Then God is a Jew, too.

Pepe isn’t sure how to answer this, not just in terms of shaping an answer so a child can understand it, but, we feel as though he isn’t entirely sure himself how a justification can be made to hate all Jews in the face of such a rational line of thinking. The theological repercussions of Pepe’s savior being a Jew, an ethnicity he’s defiled, defamed, and degraded, is too powerful to consider by Pepe, who conveniently disregards exploring it further.

Before exploring other philosophical quandaries, and looking at some of the technical and aesthetic aspects of the filmmaking itself, it’d be imprudent to go much further without stepping back and fleshing out the film’s plot itself. As we analyze and offer commentary on the film’s content, it’s crucial to know the overlying storyline that holds it together as a work, and gives the genesis for the greater ideas and concepts it in turn presents us. Living in France with his parents during the Nazi occupation, we meet Claude, an 8-year-old boy. In the beginning act they’re living in an attic, attempting to remain hidden and concealed, yet Claude’s wild behavior threatens to expose them all. The parents decide it’d be in Claude’s best interest to temporarily live elsewhere, in fears he may be sent to Auschwitz or somewhere else, arranging for him to live with an old farming family.

Claude has to take on a new identity, receiving a new last name that conceals his Jewry, learning some rituals of Catholicism like the Lord’s Prayer, and is warned not to let anyone see his circumcised penis (which is represented cleverly later as young Claude fiercely opposes any help during a bath). The elderly Pepe and Meme take him in graciously as their own, and, during their time together they build a strong and mutually affectionate bond. Pepe believes World War II is the fault of Jews (as well as his other sworn enemies, communists, Freemasons, and the British). Pepe stringently pushes his anti-Semitism onto young Claude, who typically undermines it with his youthful playfulness, teasing the old man subtly about his prejudices while never letting on his own true identity.

The film has several contrasts at its heart, several of which strike a very delicate balance, while others are arguably more clichéd but familiar story devices. There are five main contrasts worth examining: old age/childhood, humor/potential crisis, country/city, joyous bonding/hidden secrets, and Gentile/Jew. The first contrast is old age and childhood, demonstrated superbly throughout the film with the relationship of Pepe and Claude. Pepe brings with him wisdom and experience, earned from years of labor and love, while Claude exemplifies the curiosity and energy of youth. This particular contrast is crucial to the film working, as with two elderly or childlike actors in the roles, it’d dramatically deflate the film’s powerful message. It also goes to show that while Pepe is the wiser of the two, when it comes to his bigotry, his intellectualism is challenged. The second contrast is humor and potential crisis. Humor is used throughout the scenes of Pepe and Claude together; it alleviates the mood, distracting from the very real concerns of the time. Pepe and Meme have very likely not had young children around in a long time, to have the exuberant young Claude running around brings joy and laughter back into their house. On the opposite side of the coin is the severity of what may happen if Claude’s Jewish ancestry is unveiled, accidentally or otherwise, or if news comes that his parents have been captured or potentially worse. Their entire existences rests on a fragile line, with the potential to slip, going from playfulness and contentment, to anger and disillusionment.

The third contrast deals with the environmental and setting differences, simplified to country and city. In many films throughout time we’ve been given stereotypical portrayals of both city and country folk. Here, Claude comes from the city, accustomed to a faster-paced lifestyle, running around when he can with neighborhood kids in the streets, getting into mischief, etc. When he arrives in the country life is lived at a slower speed and appears simpler. It’s not all picturesque and serene, he still has to deal with bullies, kids that throw objects at Claude and chase after him. But, there’s definitely a shift, although Claude seems to transition fairly nicely into his new surroundings. The fourth contrast is somewhat similar to the second, this one being between joyous bonding and hidden secrets. Claude is welcomed with open arms by both Pepe and Meme, they take him in as own of their own, and over time, there’s no doubt they’ve grown close through their shared experiences. Everyone comes out of this period together better for it. But, underneath Claude’s usual mischievous smile or happy embrace, lies his dangerous secret, that the identity he’s living is a lie. What would have happened had he reveled his true self – that he was in fact a Jew all along? We’ll never know, but that very question straddles the contrast that marks the distinction between the bonding and hiding of secrets. The last major contrast I identified was Gentile and Jew. It can, in many ways, be tired back directly into some of the previous contrasts. One on hand, we have an anti-Semite, one who claims he can smell any Jew in his immediate vicinity, and on the other, a young Jewish boy, forced to conceal his real background. It’s this contrast that makes the movie work; it’s the basis for the story, which takes shape and grows from our understanding of it. Taken all together, the many contrasts are useful in making the film more engaging, they provide the intrigue that makes the material so fascinating and deeply affecting.

The cinematography and sound in the film are rather perfunctory; the saving grace is in the acting and the director’s firm grip on storytelling. Cinematographer Jean Penzer shoots the film in black and white, which at times is rather effective and gorgeous. It definitely adds a sense of timeliness to the film that it would have lacked in color. The film starts with a voiceover from Claude as a man looking back, as though the story is told through his remembrances, which would also make the historical quality the black and white photography gives the film appropriate. In the beginning it was obvious there wasn’t going to be a lot of camera trickery, during the scenes in the attic with Claude and his parents, it almost felt as if they were on a stage performing theatrically, the camera remained back without many cuts, letting us view the scene from a slightly detached spectatorship. George Delerue’s score is fairly understated, generally doing a nice job of mirroring the film’s many moods, only getting in the way when it drifts into sentimentality, as in the scene where Pepe and Claude are outdoors seeing to the rabbits.

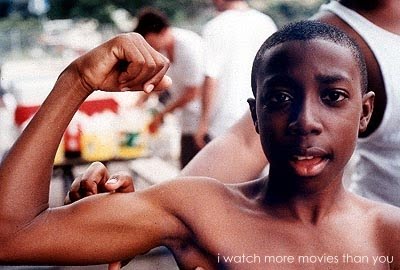

The acting as previously stated is very good and noteworthy. Michel Simon, as Pepe, is a joy to behold. Simon was nearing the twilight of his career, but at this point had a sturdy reputation in the industry as a wonderful character actor. He has a persona that threatens to overwhelm the screen, bringing the character of Pepe to life in wonderful ways. Although most won’t agree with Pepe’s personal politics, it’s hard not to like the old man, who despite his flaws and stubbornness, is undeniably loveable and shows a genuine affection towards young Claude. Alain Cohen was plucked from a Hebrew school to play Claude and delivered a tremendous performance. The DVD came with an informative booklet, included in it is an essay titled “The Two of Us: War and Peace” by David Sterrit, who says, “Cohen gives one of the all-time great child performances, conveying a wide array of emotions with his expressive mouth and shining dark eyes.” I agree wholeheartedly. Young Cohen brings all the verve of childhood to the forefront, while also feeling natural in quieter scenes, such as relaxing next to Pepe after playing out in the fields. When Meme pleads with Claude to allow her to help wash him to speed up the process, he covers himself and sulks down in the water for protection, but it’s the knowing look in his eyes as she leaves that says so much. I won’t soon forget when young Claude wakes fervently from a nightmare, rushing into Pepe’s room, waking him up startled, “I was afraid I was one of them!” he cries in terror, when asked whom he’s referring to, Claude answers matter-of-factly, “A Jew!”

The Two of Us concludes somewhat abruptly and is open-ended. We see Claude being picked up and leaving with his parents. David Sterrit, in the aforementioned essay, said, “(the film) refuses to spell out what might follow for the characters, allowing us to imagine their futures for ourselves.” Famed movie critic Roger Ebert reviewed the film twice, once when it was initially released, and then again in 2005 when he inducted it in his list of “Great Movies.” In his first review he championed the ending for being anti-Hollywood, “The ending is happy, but it isn't phony. If Hollywood had done this film, the old man would have discovered at the end that the boy was Jewish. Then there would have been a fine liberal curtain speech about the brotherhood of man.” And upon revisiting the film over thirty years later, Ebert had this to say on the film’s ending, “He (Pepe) is not converted in his thinking by this movie, and one of its strengths is that it ends without him ever becoming enlightened. Such a scene of discovery would be a sentimental irrelevance, because the movie is not concerned with what Pepe knows but with who Pepe is; the person who learns and grows is Claude.”

I included these quotes as I think they shine a light on the open ending. Generally, open endings aren’t a device used often in films, people tend to want closure and typically get it in some form. But, this film works in the way of a snapshot, similarly to Richard Linklater’s beautiful Before Sunrise (1995), which focuses on one single night a man and women spend together walking and talking through Vienna. In The Two of Us, we get a glimpse into a life-altering relationship between an elderly man and young boy, to know of what happens in the future is of no real consequence or importance beyond general curiosity. In the film’s brief running time of 87 minutes it packs an emotional wallop and the ending, while sudden, seems fitting.

In closing, amongst its brethren in the category of Holocaust-related films I feel The Two of Us has its own unique niche and place. While many of the films I’ve seen dealing with the atrocity bring the viewer into the hellish living conditions of the camps, as well as show the humiliating and brutal treatment of detainees, Claude Berri chooses not. In fact, with the exception of a select few snippets of dialogue, the Nazis aren’t referred to often and are never seen. Berri was more interested in telling a tale that appeals to the human condition, dealing with what it meant to be a Jew during a tumultuous time in history, and ultimately did it in an original and touching way.

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)